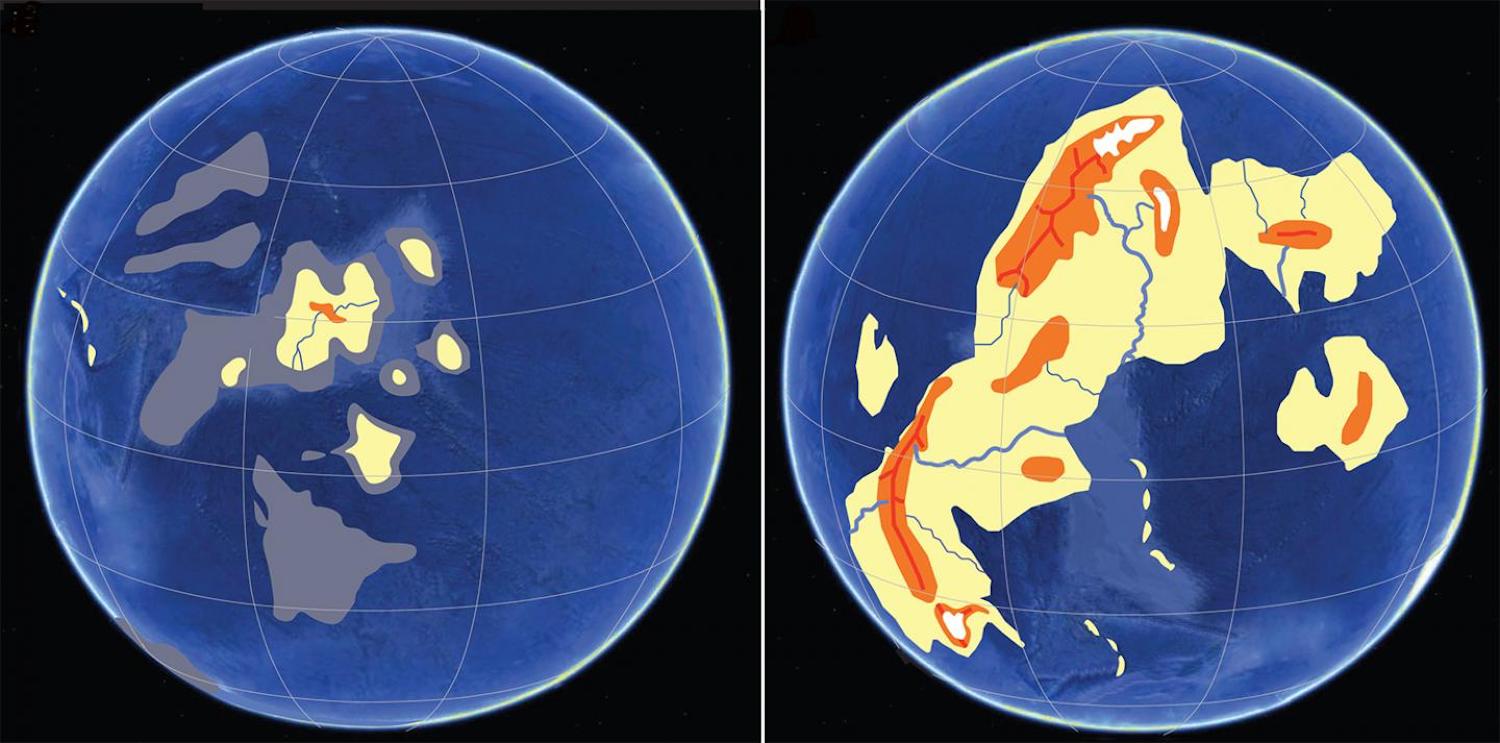

Kenorland, the first supercontinent was formed 2.4 billion years ago and this is how all the changes took place

Earth was primitively a giant ball of water with the huge amount of methane in its atmosphere. But 2.4 billion years ago, things began to change as the first landmass rose from the depths of the ocean, according to a study made by researchers at the University of Oregon. The study stated that the changes in the viscosity and temperature of the mantle resulted in the emergence of land. About 2.7 billion years ago, the mantle was still too hot and soft that it couldn’t support plateaus and large mountains ranges, however, around 2.4 billion years ago, Earth’s mantle began to cool down. This hardened the core and gave rise to a large swath of land which came to be known as Kenorland, the first supercontinent.

Ilya Bindeman, the lead researcher involved in this particular study stated that the thickness is crucial for the crust to stick out of the water. The thickness of the crust depends upon a number of reasons such as viscosity and thermal regulation. Further, the findings contradict earlier beliefs that the first supercontinent was formed around 2.7 billion years ago. Moving forward, once the supercontinent came into existence, the landmass consumed all the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere which led to the arrival of complex forms of life such as fungi, plants, algae, etc.

Researchers state that this is the time when the Earth shifted from one-celled creatures aka Archean Eon to Proterozoic Eon i.e. prokaryotes which is a primitive form of life. Being a supercontinent, the land reflected most of the light hit by the sun which contributed to one of many reasons behind Earth’s radiative balance. Researchers suggest that due to the radiative-greenhouse imbalance, the first snowfall on Earth was seen between 2.4 billion and 2.2 billion years ago.

The sudden spike in the amount of carbon dioxide resulted in the formation of more oxygen which is crucial for sustaining life on Earth. Researchers studied 278 samples of shale, world’s most common sedimentary rock that was collected from all over the world. These samples provide details on the weathering pattern observed over time. The study made by researchers at the University of Oregon is published in the journal Nature.