Ancient Bristle Worm opens up the door to an evolutionary puzzle

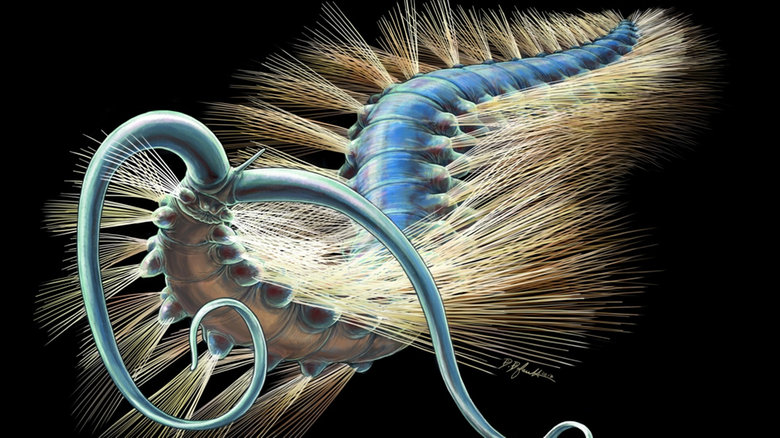

Scientists have recovered and studied beautifully preserved fossils of a weird yet soft-bodied worm in the British Columbia of Canada. Similar to any other bristle worm, this newly excavated creature has bristles coming out of his body that is the size of hairs. However, the weird thing about this worm was that its head was also partially covered by hairs and mostly near the mouth area. This worm has an eyeless form similar to an alien that has two tentacles coming out from its head. The creature lived about 508-million years prior today.

The researchers analyzed the fossilized remains of this worm to be able to solve the mystery behind the evolution of ringworms with earworms and leeches included. The main aim of the study was to know how these creatures evolved their heads, explained the lead author of the study, Karma Nanglu, who is a doctoral student from the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Toronto as well as a researcher in the Royal Ontario Museum. The analysis of this new worm suggests that these worms developed their head on the posterior side of the body segment which contained pair bristles in bundles. This hypothesis was backed by developmental biology behind the modern species of annelids.

The fossils of about 500 worms of bristle kind were found in the site located near the Burgess Shale between the years 2010 and 2016 at the place known as Marble Canyon. Nanglu said that the fossils found near the Burgess Shale are of rather great significance which documents a phenomenon named the “Cambrian Explosion” which was the first ever appearance of the ultra-modern fossilized animal groups.

The bristle worm had a length of just 2.5 centimeters, however, even with a tiny body, the worm sported numerous bristles. Each section/segment of the body had more than 56 bristles ending with two tentacles on the head. Smaller antennae present between the tentacles enabled the worm to scan an area at the direct range of its head. The tentacles had the capacity to extend farther than the antennae.

The critter was named Kootenayscolex barbarensis by the scientists. The creature has been named such with relevance to the location it was found which was the Kootenay National Park in the British Columbia. The word “scolex” is Greek for the word “worm”. The species part of the name was given in honor of Barbara Polk Milstein who volunteers at the Royal Ontario Museum. She helped with the Burgess Shale research work with the lead author Nanglu as well as his colleagues.

The bristle worm was most probably a feeder of the deposits of mud present in the seafloor. K. barbarensis mostly funneled its mouth into the mud while sifting through the organic material contained inside it and feeding on it. The evidence for this was found in the gut remains that were well preserved. The findings of this research were published in the journal named “Current Biology”.