In order to meet US space agency NASA’s requirements for certification, Boeing and SpaceX have successfully conducted parachute testing.

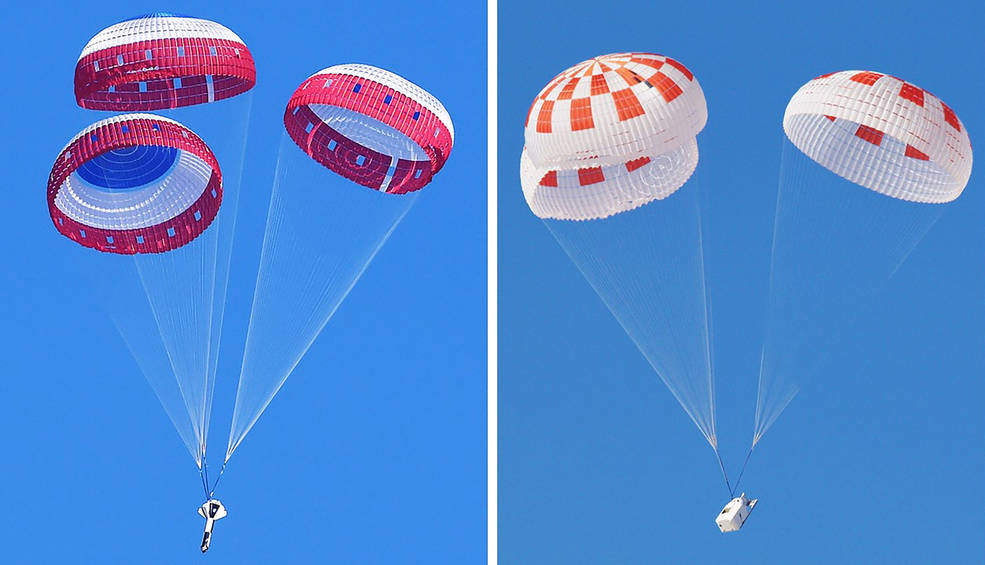

On March 4, SpaceX performed its 14th overall parachute test supporting Crew Dragon development. This exercise was the first of several planned parachute system qualification tests ahead of the spacecraft’s first crewed flight and resulted in the successful touchdown of Crew Dragon’s parachute system.

During this test, a C-130 aircraft transported the parachute test vehicle, designed to achieve the maximum speeds that Crew Dragon could experience on reentry, over the Mojave Desert in Southern California and dropped the spacecraft from an altitude of 25,000 feet. The test demonstrated an off-nominal, or abnormal, situation, deploying only one of the two drogue chutes and intentionally skipping a deployment stage on one of the four main parachutes, proving a safe landing in such a contingency scenario.

In February, the first in a series of reliability tests of the Boeing flight drogue and main parachute system was conducted by releasing a long, dart-shaped test vehicle from a C-17 aircraft over Yuma, Arizona. Two more tests are planned using the dart module, as well as three similar reliability tests using a high fidelity capsule simulator designed to simulate the CST-100 Starliner capsule’s exact shape and mass. These three tests involve a giant helium-filled balloon that lifts the capsule over the desert before releasing it at altitudes above 30,000 feet to test parachute deployments and overall system performance.

In both the dart and capsule simulator tests, the test spacecraft are released at various altitudes to test the parachute system at different deployment speeds, aerodynamic loads, and or weight demands. Data collected from each test is fed into computer models to more accurately predict parachute performance and to verify consistency from test to test.

Mark Biesack, a lead NASA engineer at Kennedy Space Center overseeing parachute testing for the agency’s Commercial Crew Program said, “We test the parachutes at many different conditions for nominal entry, ascent abort conditions including a pad abort, and for contingencies, so that we know the chutes can safely deploy in flight and handle the loads.”

SpaceX will conduct its next parachute system test in the coming weeks in the California desert, again using a C-130 to drop the parachute test vehicle from about 25,000 feet. The test will be similar to the one conducted earlier this month, but with a different deployment configuration. The test will intentionally skip deployment of one drogue parachute and one main parachute to further demonstrate SpaceX’s ability to safely land the vehicle in an off-nominal situation. The ongoing testing verifies the safety of the parachute system for our astronauts.

Boeing is scheduled for its third of five planned qualification tests of its parachute system in May, using the same type of helium-filled balloon that will be used in the reliability tests. For the qualification test, the balloon lifts a full-size version of the Starliner spacecraft over the desert in New Mexico before releasing it. The balloon lifts the spacecraft at more than

1,000 feet per minute before it is dropped from an altitude of about 40,000 feet. A choreographed parachute deployment sequence initiates, involving three pilot, two drogue and three main chutes that slow the spacecraft’s descent permitting a safe touchdown.

Both Boeing and SpaceX’s parachute system qualification testing is scheduled to be completed by fall 2018. The partners are targeting the return of human spaceflight from Florida’s Space Coast this year, and are currently scheduled to begin flight tests late this summer.

“The partners are making great strides in testing their respective parachute systems, and the data they are collecting during every test is critical to demonstrating that their systems work as designed,” said Kathy Lueders, Commercial Crew Program Manager at Kennedy Space Center. “NASA is proud of their commitment to safely fly our crew members to the International Space Station and return them home safely.”

NASA’s Orion Program, which is nearing completion of its parachute tests to qualify the exploration-class spacecraft for missions with crew, has provided Commercial Crew Program partners with data and insight from its tests. NASA has matured computer modeling of how the system works in various scenarios and helped partner companies understand certain elements of parachute systems, such as seams and joints, for example. In some cases, NASA’s work has provided enough information for the partners to reduce the need for some developmental parachute tests.

The goal of the Commercial Crew Program is safe, reliable and cost-effective transportation to and from the space station from the United States through a public-private approach.